What Brian Flores is really fighting for

The NFL has a genuine diversity problem in its senior coaching and team executive ranks, according to the NFL.

"Any criticism we get for lack of representation at the GM and head coach positions, we deserve," Jonathan Beane, the league's senior vice president and chief diversity and inclusion officer, told the Associated Press in January. "We see that we're not where we want to be. We have to do much better."

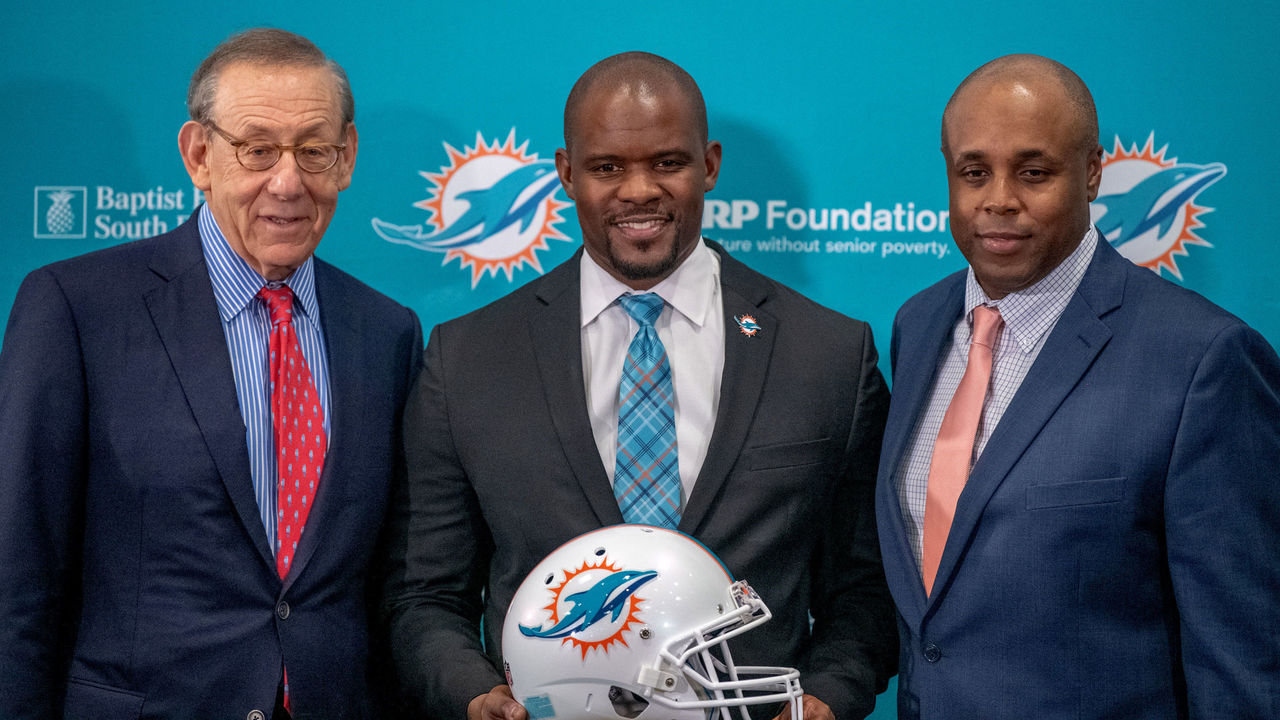

Beane's words were included in a racial discrimination lawsuit that former Miami Dolphins head coach Brian Flores filed this week. The league responded a little more than an hour after Flores' suit hit the internet, declaring it "will defend against these claims, which are without merit."

The suit bores into a problem that the NFL acknowledges is genuine. But rather than delve into Flores' claims with any kind of inward-looking inquiry - it reportedly will investigate Flores' allegation that Dolphins owner Stephen Ross offered him monetary incentives to lose games in 2019, which is a separate (and potentially explosive) matter - the league chose to do what it does best: lawyer up and window-dress.

"The NFL and our clubs are deeply committed to ensuring equitable employment practices and continue to make progress in providing equitable opportunities throughout our organizations," the league also said in its response to Flores' suit. "Diversity is core to everything we do, and there are few issues on which our clubs and our internal leadership team spend more time."

Flores has taken a swing at ownership, and ownership is a protected class when it comes to the NFL's scattershot application of discipline. For years, Dan Snyder basically ran the workplace inside Washington's organization like a bachelor party, and the league couldn't be bothered to produce a written report after it finally investigated.

Racist hiring practices? Sham interviews designed to do an end-around on the Rooney Rule? Not possible. Not in a league so "deeply committed" to diversity and equal opportunity that it stencils "End Racism" into the end lines on game day.

The league's approach to racial equity has always been hollow and self-serving, and Flores' complaint documents this in great detail, going all the way back to the "gentlemen's agreement" that kept Black players out of the game in the 1930s and 1940s.

The last five years alone included the blackballing of Colin Kaepernick; the imposition of an anthem policy that was never enforced because the players' union was determined to resist it; the revelation that race-norming was used to limit the league's financial exposure in the concussion settlement; and commissioner Roger Goodell's cynical embrace of the Black Lives Matter movement, which happened only after it became safe for corporations to attach themselves to racial justice causes as marketing opportunities.

The Rooney Rule might be well-intentioned, but it was only instituted after the NFL was threatened with a lawsuit more than 20 years ago. There's nothing new about the possibility that teams might arrange phony interviews with minority candidates to stay in compliance with the rule, which coaches like Marvin Lewis are now willing to discuss openly. The fallout from the texts Flores received from Bill Belichick, in which Belichick congratulates Flores on getting the Giants job before admitting he thought he had messaged Brian Daboll, simply seems to confirm a truth that's long been easy to suspect.

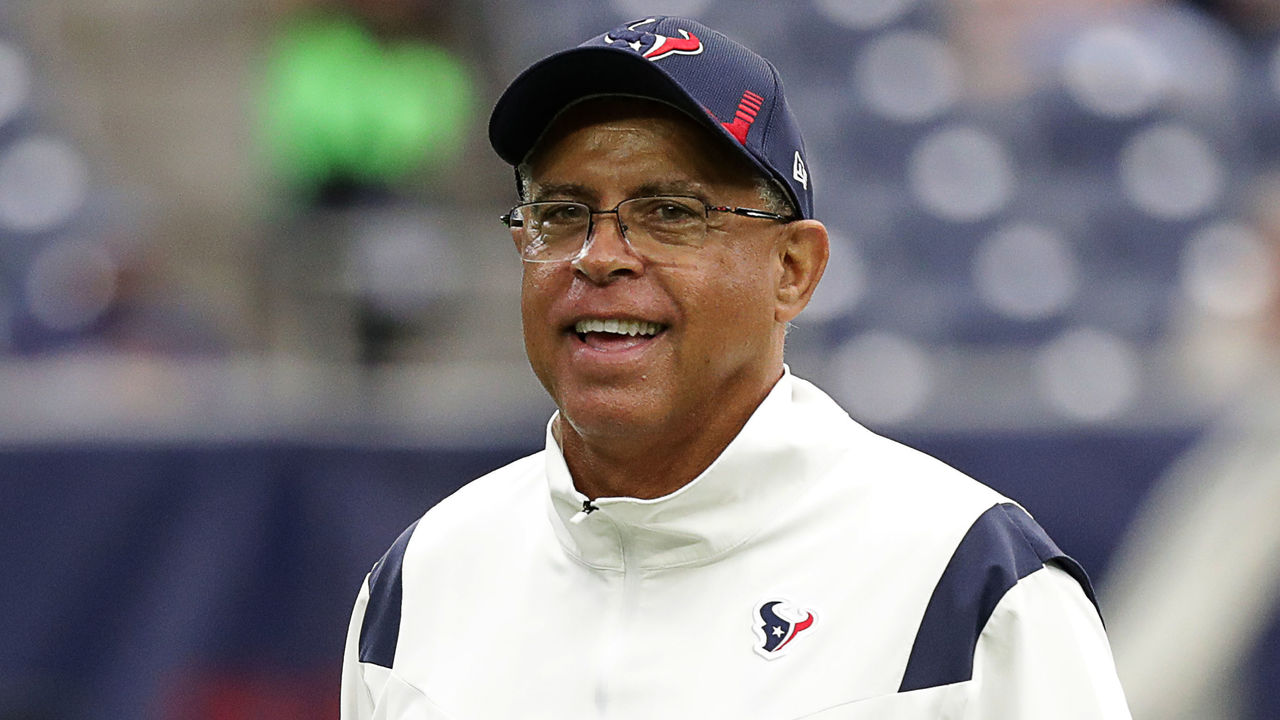

According to the league's own diversity and inclusion report, more than 70% of the league's players are Black, yet the NFL currently has just one Black head coach, four Black offensive coordinators, 11 Black defensive coordinators, and three Black quarterbacks coaches. The league is in a two-year cycle in which 16 head coaching positions opened up, yet it's possible that David Culley will remain the only Black candidate to get hired - and the Texans fired him after just one season.

Flores' suit observes that Black head coaches are more likely to get fired after having a winning season and less likely to receive multiple head coaching opportunities. And coaches like Flores, Culley, Hue Jackson, Steve Wilks, and Vance Joseph recently served as placeholders during what were billed as long rebuilds.

The league has long imagined itself as a true meritocracy whose hiring decisions are zero-sum matters of winning and losing in which only the best candidates are awarded such high-pressure jobs. But nepotism and cronyism run rampant, as is true in a lot of industries. I wrote about this two years ago, and in January, Defector's Kalyn Kahler documented the true scope of the problem:

Overall, the league averages 3.4 coaches per team who are related to a current or former NFL coach, and the percentage of coaches at the supervisory levels - the ones with hiring power - is even higher. Eleven of 32 head coaches are related to a current or former NFL coach. There are 24 coordinators who are related to current or former coaches, almost a full quarter of them.

This is true of both of this year's Super Bowl coaches. The Bengals' Zac Taylor is the son-in-law of former NFL head coach Mike Sherman, while the Rams' Sean McVay is the grandson of a former NFL head coach and team executive. Taylor and McVay have obviously proved to be capable coaches, but there's no denying they both got a foot in the door at someone else's expense because of these connections.

Having a connection isn't necessarily a bad thing. But it points to how much easier it often is for white coaches to get into the profession, since more of them are likely to have those ties.

Rod Graves, director of the Fritz Pollard Alliance - which promotes minority hiring in the NFL - suggested to Kahler that coaches sharing the same agent is an even bigger problem than family connections. Graves, who is Black, is the former Cardinals GM. He got his start in the NFL because his father, Jackie, was once a scout and personnel director for the Eagles. A quick glance at the extensive client list of coaches and executives represented by superagent Bob LaMonte lends credence to Graves' point.

So does Flores' case have a chance? The odds are stacked against him, according to Brad Sohn, a Florida lawyer who has taken on the NFL on behalf of numerous players.

Sohn noted to theScore that the suit was filed as a class action, with Flores' lawyers asserting that more than 40 plaintiffs will be willing to come forward. But in legal parlance, a class action means each plaintiff has sustained identical harm, whereas in this case, each individual plaintiff will likely have a specific sort of claim.

For another, Flores is going to have a hard time proving racial discrimination is the reason he didn't get the Giants' job that went to Daboll.

"Look, there's a lot of sort of circumstantial evidence on that point, perhaps," Sohn said. "But I see it as a completely onerous standard. The Giants can point to everything from 'Brian Daboll was just a better fit for what we wanted to do as an organization,' maybe they wanted an offensive guy, they can point to the fact that they had a Black general manager (Jerry Reese) for a long time. That's a really steep challenge."

The Giants have since put out a statement reiterating that they hadn't interviewed Daboll in person until the day after Belichick texted Flores, which the team asserts is proof that Daboll hadn't yet earned the job. Of course, these are the ambiguities that allow structural racism to continue to flourish. Flores knows this. When MSNBC's Chris Hayes asked him what the best outcome to all this would be, this was Flores' answer:

"We create real change. It's not policies; I don't want fluff. That starts here in the heart, and you only get that through conversation, through dialogue, through communication. And I'm open to communicate with whoever it is about what it's like to walk into that type of interview, what it's like for Black and minority leaders on the field. … There's so many qualified and capable leaders on many different staffs in this league, and we've got to be intentional about giving them this opportunity."

By filing suit, Flores is communicating in the only language the NFL truly understands.

Dom Cosentino is a senior features writer at theScore.