How Akil Baddoo went from A-ball to the majors as a Rule 5 outlier

CLEVELAND - Akil Baddoo rested on the couch last December, watching Netflix at his parents' home in Conyers, Georgia, a suburb about 25 miles east of Atlanta. He pulled up the Rule 5 Draft tracker on his laptop.

There is not a lot of fanfare around Major League Baseball's other draft, in which players who have spent at least four or five years toiling in the minor leagues (depending on their age at signing) and who have not been added to their organization's 40-man roster can be selected by another team. There's no green room or red carpet. In non-COVID times, the draft takes place in a hotel conference room on the last day of the winter meetings.

While the Rule 5 Draft generates little enthusiasm, it does offer a direct path to the majors: Players selected in the major-league phase need to be on the big club's roster for the entire season to be retained. Otherwise, they're offered back to their original club.

Baddoo had read a story that listed him as a candidate to be selected, so he thought he'd tune in.

The first pick flashed on his laptop screen, drawing his attention away from the television: The Pirates selected right-handed pitcher Jose Soriano from the Angels. Next, the Rangers selected Brett de Geus from the Dodgers. Then Baddoo's internet connection went out.

"My screen went completely black," Baddoo said.

He was frustrated. Then he received a text message from Seth Stohs, a writer for a site that covers Minnesota Twins prospects called Twins Daily.

"He said, 'Congratulations.' I said 'For what?'" Baddoo recalled. "He said, 'You're a big leaguer.' Sure enough, my screen came back on and I saw it: 'Akil Baddoo, third pick, to the Detroit Tigers.' I'm screaming, 'Mom! Holy crap! I got picked!'"

His mom, a project manager for the payroll company ADP, asked if he was kidding. She was working from home and on a conference call; she didn't have time for jokes. Shortly afterward, she left the call.

The Tigers' selection led to one of the greatest outlier Rule 5 rookie seasons of all time. Baddoo has produced a campaign that the rest of baseball can learn from.

The Rule 5 Draft generates so little buzz because the returns are typically minimal. Since 1999, the 71 position players drafted to play in the majors have a median slash line of .206/.271/.295 as rookies. But to date, only Josh Hamilton owns a better wRC+ as a Rule 5 rookie (130) than Baddoo (115) among players who logged at least 300 plate appearances.

And Baddoo is an even greater outlier than many Rule 5 picks: Before this season, he'd never played above Single-A.

He made 131 plate appearances in 2019 at High-A before he required Tommy John surgery, ending his campaign. Then COVID-19 wiped out the 2020 minor-league season, and Baddoo wasn't chosen to play at the Twins' alternate site.

From 2010-19, only three other Rule 5 position players arrived in the majors without playing at Double-A or Triple-A, according to Baseball-Reference data. Catcher Adrian Nieto logged just 118 MLB plate appearances with the White Sox in 2014. The Padres had two such players in 2017: catcher Luis Torrens, who appeared in 56 games, and utility player Allen Cordoba, who played in 100 games. Only Torrens, the backup to Tom Murphy in Seattle, has since earned a regular job in the majors.

Those circumstances meant Baddoo had to maximize his development without relying on access to professional facilities.

Before he could start swinging a bat following his 2019 Tommy John surgery, he often grabbed his iPad and searched for every video he could find of his favorite left-handed swings and approaches: Ken Griffey Jr., Robinson Cano, and Barry Bonds. He filled a notebook with observations.

"I'm a big video guy, just watching the greatest hitters of all time," Baddoo said last weekend at Progressive Field. "I just watched them over and over. … Just looking up their swings and what made them so great, so consistent."

Once he could begin swinging in December 2019, he worked with private hitting instructor Jay Hood, who has a number of professional hitting clients in the Atlanta area. They worked on one particular drill, where Hood tossed him pitches at 45-degree angles, to force him to use the whole field.

"To be able to drive the ball, truly, to left center, to right center," Baddoo said. "I think it helped a lot."

He also focused on the mental aspect of his game. Baddoo believes that's been key to his ability to adapt and to shorten his slumps this season, especially once opposing pitchers adjusted to him after his blistering first two weeks. He began a meditation routine, and he quietly reflects "at least 30 minutes a day" to "ease his mind" and "slow" his heart rate.

"My parents talk all the time about how important it is to be relaxed when you're playing," Baddoo said. "Great things will happen when you are relaxed and having fun. … In the big leagues, yeah, the talent is a lot better, but a lot of these guys are mentally strong throughout their whole careers."

His parents are an important part of his story. He says they taught him how to work. They are first-generation Americans. His maternal grandmother was a doctor who emigrated from Trinidad and Tobago, and his father's parents emigrated from Ghana.

They taught him to appreciate data, and they're more into advanced baseball metrics than he is. After all, his mother works for one of the most important number-crunching companies in the U.S., and his dad is an engineer who passed down his love of baseball and the New York Yankees. His dad taught Akil baseball history and statistics through his extensive collection of cards, telling him all about Willie Mays, Jackie Robinson, and other legends.

"He brought baseball to me. I kind of stuck with it," Baddoo said. "It was kind of natural."

When Baddoo was 2, the family moved to the Atlanta area, an amateur baseball hotbed. Baddoo excelled at multiple sports, but it was baseball that earned him an offer from the University of Kentucky. He would have attended, but the Twins made him a second-round pick in 2016 while he was still just 17. Though his parents wanted him to get a degree, they understood his desire to chase a dream. They asked him to be smart with his $750,000 signing bonus, and place most of the cash into savings or investments.

They knew the odds of reaching the majors were low and the odds of sticking around for a long career were even shorter. But now Baddoo looks like a better bet to beat those odds.

When he arrived in Lakeland, Florida, for spring training in February, Tigers teammate Robbie Grossman said Baddoo immediately turned heads.

"What's remarkable to me, from when he showed up in spring training, Day 1, he had the tools to do whatever," Grossman said. "The amazing thing to me is his consistency with his swing, his approach. He wants to get better. He's out here every day working on things and absorbing everything we're throwing at him."

Out of the gate, Baddoo was one of the great stories in baseball. He homered on the first pitch he saw in the majors, slashing an Aaron Civale offering the opposite way over the left-field wall at Comerica Park. He flipped his bat as if he were not remotely surprised. In his first eight games, he hit four home runs and posted a 1.443 OPS.

Then he slumped. He finished April with a 43.9% strikeout rate and a 3% walk rate. Among players with at least 60 plate appearances, he had the second-highest K rate in the majors at the end of the month.

Was he destined to share the fate of most Rule 5 draftees?

Remarkably, he kept adjusting on the fly, and he's continued to get better and grow in his first exposure to the best pitching in the world.

He reduced his strikeout rate in May (29.3%) while his walk rate boomed to 24.1%, the second-best mark in the majors that month. He'd always had a good eye in the minors, but the improvement was notable. His strikeout rate dramatically dropped again in June (17.1%), falling below the MLB average. It stayed under the league average in July as well (18.8%).

Baddoo credited the improvements to chasing out-of-the-zone pitches less frequently, along with tweaking his two-strike approach: He widened his stance, choked up a little bit, and focused on the opposite field, thinking about the 45-degree-angle drill.

Through the end of April, Baddoo hit just .114 with two strikes, ranking 209th out of 271 batters who saw at least 200 pitches in the month. From May 1 through play on Aug. 9, he ranked 53rd out of 359 batters to see at least 400 pitches, batting .217 with two strikes.

"I think he is just realizing what guys are trying to do to him, and he made those adjustments on the fly, really quickly," Grossman said. "It usually takes guys longer than it took him. Now they are making another adjustment to him. I keep telling him, 'This is what might happen next. What are you going to do?'"

He's probably got more untapped power, too. While he's posted a below-average exit velocity, he possesses above-average maximum exit velocity. After the first week of April, Baddoo didn't hit for much power until July, when he began to pull the ball more and slammed five home runs.

Even with the mid-April slump and without reaching his full power potential, Baddoo was an above-average hitter based on wRC+ in each of the first four completed months of the season. His success simplified a crowded outfield situation in Detroit as he put a lock on left field, with some additional time in center.

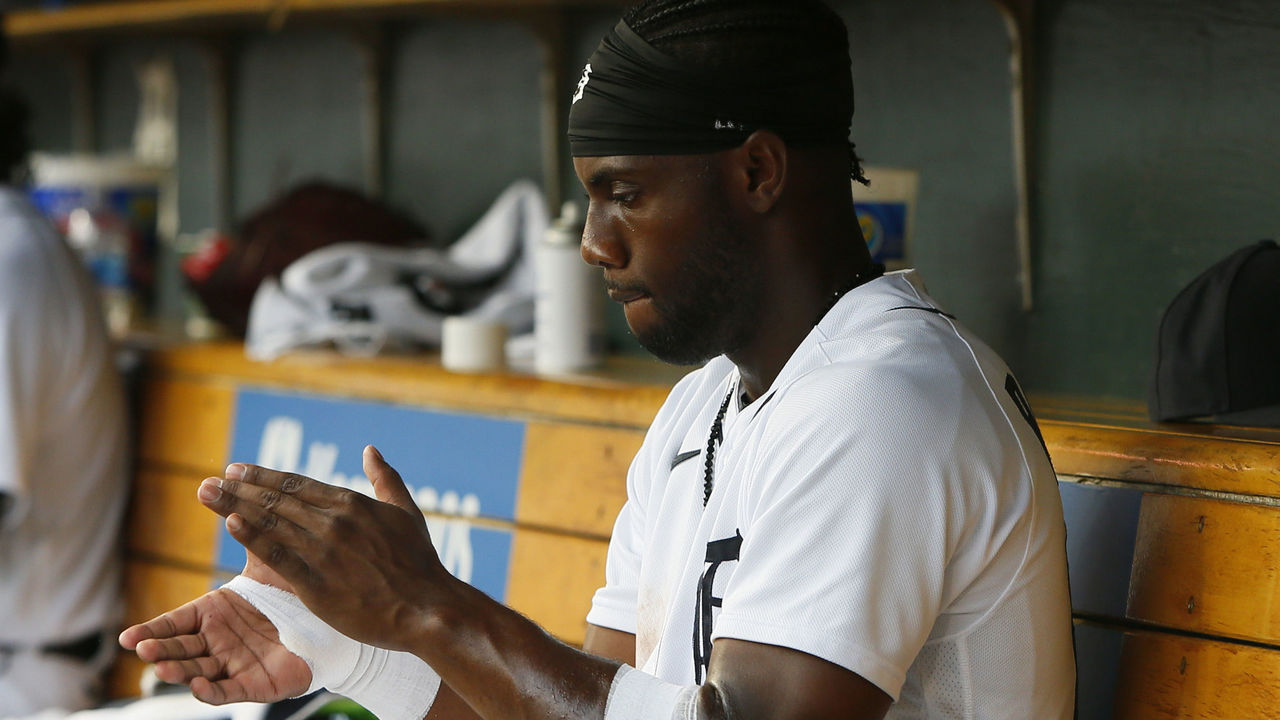

The only thing that might really derail his season is his nasty collision with Derek Hill as they chased the same fly ball during Tuesday night's game in Baltimore. Baddoo was placed on the seven-day concussion injured list Wednesday, and Hill is on the 10-day list with a rib contusion.

Still, Baddoo's success raises the question: Could more players benefit from being promoted more quickly? Could being challenged earlier accelerate their development? After all, how do you get better against major-league pitching without facing major-league pitching?

"I think you answered your own question," Grossman said. "I think the only way you get better is to play against the best. It speaks volumes about what he's done."

Constraint training is all the rage in major-league baseball; weighted-ball and long-toss routines are now commonplace. The idea is that by throwing more challenges at an athlete than they are accustomed to, their bodies will adapt to handle the stress, making them stronger, more skilled, and more efficient. Baddoo's season is a related example - few players face the sink-or-swim challenge of being a Rule 5 pick.

Does he feel others could follow in his footsteps?

"I feel if you put your mind to something, you can do anything," Baddoo said. "It doesn't matter if you're at Low A, rookie ball - if you got your mind into it, and you're working, not letting up, anything is possible."

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.

HEADLINES

- Bassitt helps Jays hand Yankees 1st back-to-back losses

- MLB Power Rankings: Yankees look great, Houston's got a problem

- Longtime Yankees voice John Sterling retires

- Rockies' Freeland fine after collision at plate as pinch runner

- Robinson remembered on 77th anniversary of breaking baseball's color barrier